A man's real possession is his memory; in nothing else is he rich, in nothing else is he poor." (Alexander Smith)

Noa Yekutieli continues to focus on the concept of the home and memory and how they change according to our emotional and social needs. Yekutieli does not use her personal, immediate memory, but the memories of others who have experienced irreversible, dramatic moments. She presents a series of natural disasters which took place in the past century (the collapse of houses, earthquake, landslide, tsunami, flood, drowning, tornadoes, etc.): sudden, powerful disasters which sow destruction and ruin in the environment and on the whole cannot be anticipated. She chooses images of disasters from around the world, in different times and places. In all of them the physical, national, and economic or social disaster becomes personal and its consequences change the individual's fate once and for all. However, disasters, despite being local, create a universal experience, a common denominator and collective memory for people from different physical, emotional and historical places.

Disasters, and the consequent physical and emotional trauma, increase our need to preserve memories, "Because that's what's left," says Yekutieli and adds, "When a disaster happens, reality changes. The geographical environment and human nature are able to rebuild themselves and turn over a new leaf which tries to make you to forget the pain of the tragedy and loss that have taken place. We make an effort to preserve whatever is possible – memories made up of many pictures are reduced over time to single pictures."1 A single image encapsulates situations full of sights, sensations and emotions. Memory is a subjective and personal process, influenced by the importance that a person attaches to things and it has many roles in building and structuring the self. "Memory has a decisive importance regarding all cognitive activity and it is essential to the ability to survive... It is essential to the ability to learn in that it enables us to accumulate experience and knowledge from past experiences... In this way it enables us to understand and interpret new experiences."2 Yekutieli chooses the scenes before, during and after the disaster carefully, so that they will preserve and illustrate the experience and the broken fragments of life's memories. Through them she examines the line that divides reality from memory, an existing moment from a passing moment and the gaps and the transformation that lie between them. Yehudit Rotem in her novel, "I loved so much," writes about memory: "Memories know how to be cunning, to flee when you want to touch them. Like little fish, like curling waves near the beach that tickle your feet and melt into foam. Often, memory is an abstract knowledge of what once existed. Memory is piled on memory, shadow on shadow, until you cannot tell what is pure memory and what is the memory of a memory".3

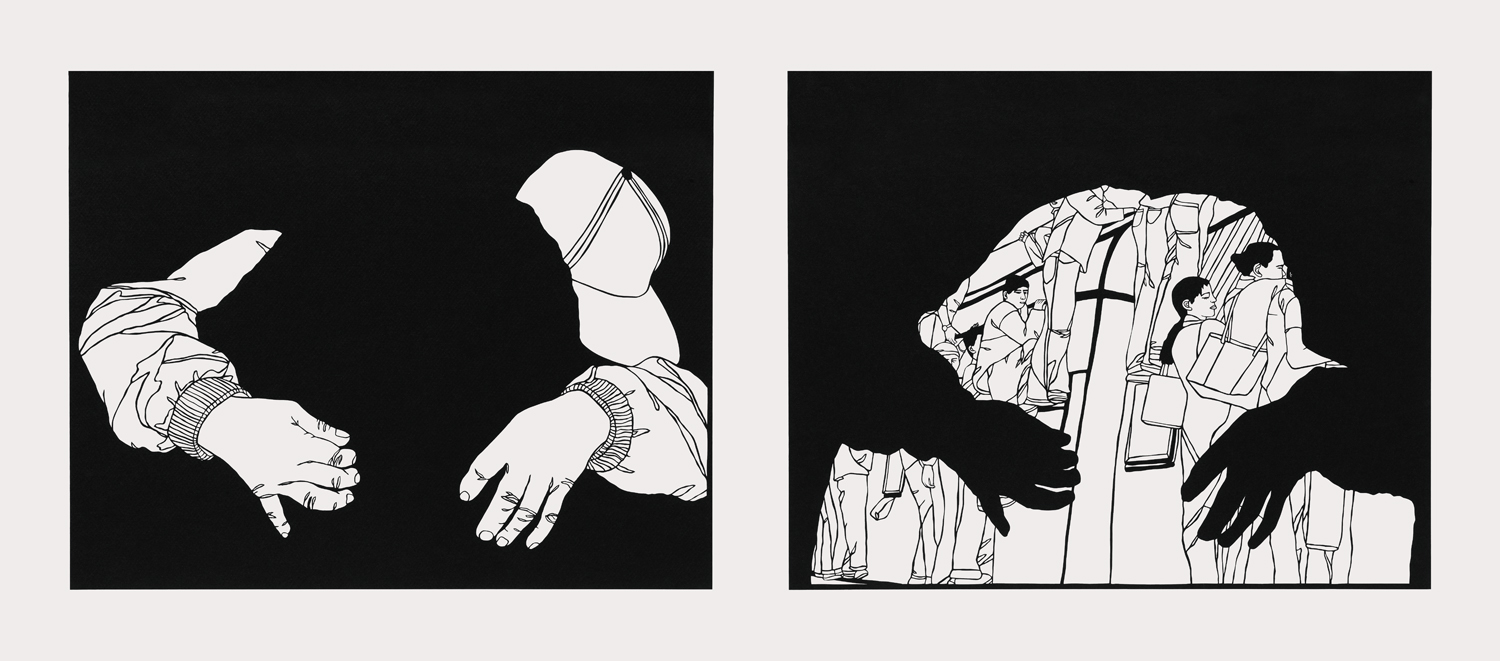

The works were inspired by photographic images from the local or international media. The use of newspaper photographs validates the events pictured; however, at the same time also points at the act of testimony itself (reality is shown from a subjective viewpoint) and Yekutieli clarifies our understanding that no testimony is objective. The artist is not directly present in the events described but experiences them through a mediator – the photographer or the photograph. The photograph forms a content-related, visual starting point and the basis for the works. "From the moment of choosing the photograph, a process takes place in which I decide how to react to the photographic text: which part of the photograph to choose, the scale, and the possible types of cuts," and she adds, "My eye translates the human space in which the future story takes place to the instant flash of the camera." Sometimes Yekutieli translates the whole scene and sometimes she severs figures from their context and creates a new context for them. In this way the "information" changes its meaning and its place.

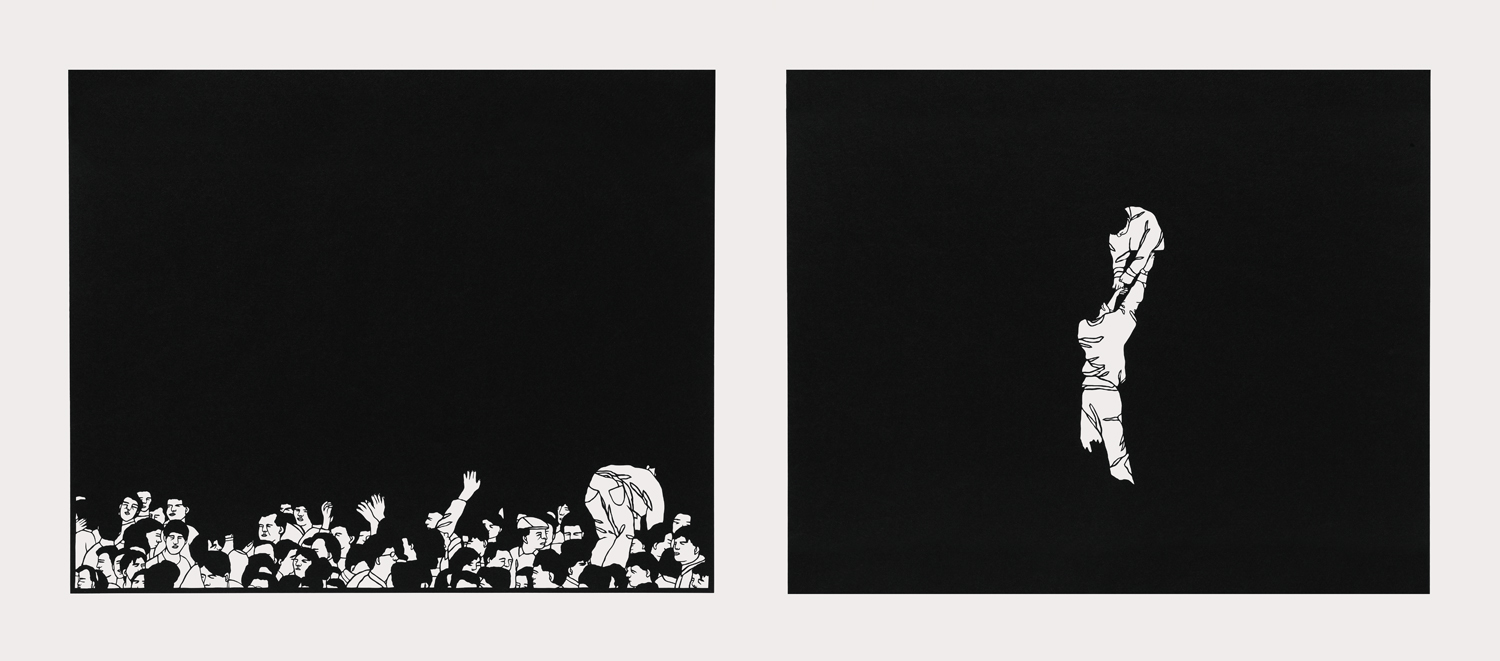

The works show situations of environmental and human suffering and destruction: in Richter's words, "Death and suffering have always been an artistic theme."4 In each picture the human element is present in an encounter with an inhuman situation. The artist portrays the figures with restrained precision, with emphasis not on facial features or a specific likeness but on their body gestures, which express differing degrees of suffering and heart-breaking restraint such as: holding hands, etc. Most of them do not directly face the viewer but are occupied with the space around them, which is mostly piles of rubble and waste. The pile becomes a silent testimony, a memory of trauma, such as war, an act of terror, an earthquake, or houses which existed and are no longer there. The pile is an abandoned still life, between life and death, between plant and stone. The works move on the axis between life and death in order to talk about life.

Yekutieli manages to encapture the body language of the universal aspects of human pain in the pictures with maximum succinctness. For instance: the comforting, strong, protective embrace becomes a physical act with universal significance beyond the actual moment. It becomes a symbol of brotherhood, help, compassion and identification mixed with intense pain; its aim is to demonstrate warmth and affection for others. The line of people holding hands, create a human chain, which enables closeness, identification and sharing, a strong feeling of community and togetherness. The means of coping with the disaster at national and personal levels are culturally dependent, such as, for example, in customs and expressions of mourning or affection. "I bring together different people, with different reactions, and create contact and discourse that hardly ever happens in reality." In the series, each work is composed of a large number of figures gathered together in an shared, assymetric composition. In each such work a nonsequential, non-didactic series of events and images of the moment of the disaster and the moment of healing and human compassion can be seen. Horror and beauty meet In each work. She avoids any expressive dimension by using a precise compositionary cut. The decisively non-modern character of the technique emphasizes its content.

The works, built using a strong contrast of black and white, use a manual papercutting technique, carried out with a utility knife, which requires precision and accuracy. The technique of papercutting has a long history, apparently originating in China and the Far East, through Jewish folk art (papercuts were very popular among the Jews of Eastern Europe in the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century), and is frequently referenced in postmodern art.5 Yekutieli utilizes the aesthetics and the harmony of the technique to transmit the difficult, complex themes of destruction, trauma and memory. This duality creates tension in the works, which is increased by the choice of a simple, uniform, black paper backing rather than a possible variety of colors; by choosing a cutting knife rather than a paintbrush or a sculpting chisel; and the decision to remove and subtract from the whole sheet, as a means of creating a picture. The artist opens holes and cracks, and turns the black paper into a multi-expressive platform. "What I like about this technique is the existence of the concept of 'temporariness.' As in life, you make a decision and there's no return. You can only subtract and it's hard to add. The absence, the nothingness, the holes in the story and in memory, create existence, the story and what remains ... When there are holes in the story and not everything is systematic, we remember forgotten things," says Yekutieli. The cut paper symbolizes the traces of memory that we have chosen to retain, delineating in the end a single, subjective scene (as part of the collective experience).

Natural disasters, because of their strength, often demolish the physical and mental home that carries memories of place and time. People want to preserve what no longer exists; life's memory is composed of thousands of moments which fall apart and are reassembled simultaneously. This is comparable to the papercutting technique in which lines join and separate to form scenes which, the longer you look at them, the clearer they become.The physical landscape shatters into thousands of pieces which are rearranged in a new order and form the landscape inside us – memory. The paper preserves personal and collective memory. "My works, in recent years, have focused on the memory that exists in life. I examine its validity, what we can preserve and contain, and what we can't." The name of the exhibition, "Between our intentions," relates to the gap between reality, the event that has happened, and intentions. "Our lives often 'go' in directions we didn't intend, they fall between the intentions, neither here nor there, inbetween." This gap is comparable, in Yekutieli's view, to the gap between the memory and "reality," between the subjective and the objective, between the moment before and the moment after. The large works show compressed environments, which create a sensation of suffocation and crowding, where the local and the universal, the realistic and the imagined, are intertwined in an invisible thread.

Comments:

• All the quotations are taken from a conversation with the artist on the occasion of the exhibition, in a studio in Tel Aviv, January 2014.

• From the entry: Memory, Wikipedia.

• From: Yehudit Rotem, I loved so much, Yedioth Aharonoth-Hemed books, 2000.

• Gerhard Richter: Text, writings, Interviews and Letters1961–2007, Thames & Hudson, London, 2009, p.227.

• See, for example, works by Kara Walker who examines problems of gender and sex through this technique, or the decorative and naive works of Beth White or the poliitical works of Roee Rosen and Larry Abramson, etc.